Investor Insights

SHARE

Market narrative to pivot from peak inflation to recession

Twelve months ago, official cash rates sat at record lows and only one English-speaking Central Bank – the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) – had commenced the tightening process in response to increasing inflationary expectations. The rapidly rising commodity prices coinciding with the war in the Ukraine (commenced 24 February 2022) finally got the attention of the English-speaking Central Banks and they followed the RBNZ typically with 8 or 9 “interest rate increases” over the balance of 2022.

Today, we have a situation where the official cash rate for the five English-speaking Central Banks, New Zealand, USA, UK, Canada and Australia, averages 3.87 per cent, with a range from 3.10 per cent (Australia being the lowest) to 4.25 per cent (New Zealand, the US and Canada). With the exception of the RBA, these are the highest official cash rates since 2008, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) really got going.

|

New Zealand Date |

% |

USA

Date |

% |

UK

Date |

% |

Canada

Date |

% |

Australia

Date |

% |

|

2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6/10 |

0.50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24/10 |

0.75 |

|

|

16/12 |

0.25 |

|

|

|

|

|

2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23/2 |

1.00 |

17/3 |

0.25 |

3/2 |

0.50 |

26/1 |

0.25 |

6/4 |

0.35 |

|

13/4 |

1.50 |

5/5 |

0.75 |

17/3 |

0.75 |

2/3 |

0.50 |

8/6 |

0.85 |

|

25/5 |

2.00 |

15/6 |

1.50 |

5/5 |

1.00 |

13/4 |

1.00 |

5/7 |

1.35 |

|

13/7 |

2.50 |

27/7 |

2.25 |

16/6 |

1.25 |

1/6 |

1.50 |

2/8 |

1.85 |

|

17/8 |

3.00 |

21/9 |

3.00 |

4/8 |

1.75 |

14/7 |

2.50 |

6/9 |

2.35 |

|

5/10 |

3.50 |

3/11 |

3.75 |

22/9 |

2.25 |

8/9 |

3.25 |

4/10 |

2.60 |

|

23/11 |

4.25 |

14/12 |

4.25 |

3/11 |

3.00 |

27/10 |

3.75 |

1/11 |

2.85 |

|

|

|

|

|

15/12 |

3.50 |

7/12 |

4.25 |

6/12 |

3.10 |

|

Number of increases |

9 |

|

7 |

|

9 |

|

8 |

|

8 |

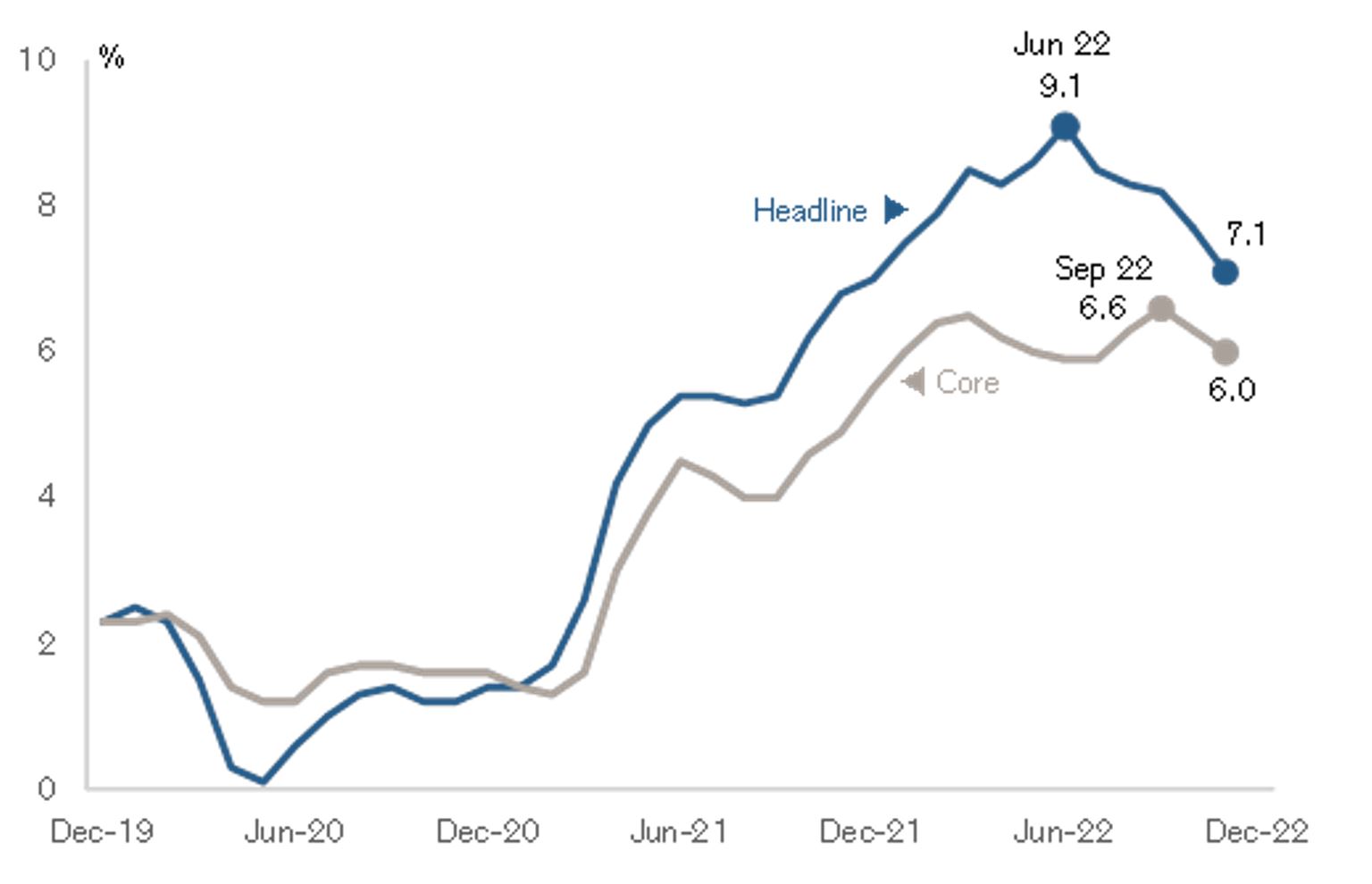

Now we have early indications of declining inflationary expectations in the US which probably means further increases of Central Banks’ official cash rates in the March 2023 Quarter will be quite muted.

Nevertheless, with a move from an average official cash rate of virtually nil to an average expected to exceed 4.0 per cent in the near-term – post around nine separate increases in approximately twelve months – we are likely to see the market’s concern shift from “peak inflation” to “recession”.

Economic conditions in 2023

As investors, we need to ask ourselves what are the ramifications of recessionary economic conditions in 2023; and to what degree this has already been priced into the market? What I mean by this, for example, is to what degree has the twelve-month share price decline (to 15 December 2022) of 65 per cent for Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook), 51 per cent decline for Netflix, 48 per cent decline Amazon, 37 per cent decline for Google and 23 per cent decline for Microsoft, assumed a severe slowdown in demand by the consumer?

Importantly, which businesses will exit the forecast recessionary conditions in better shape, relative to their competitors? These are the ones – which have a sustainable competitive advantage – the businesses which should be part of any investor’s long-term portfolio.

Given share prices tend to go up by the staircase and go down by the lift shaft, an even more important question from an investors’ perspective is which businesses will exit the forecast recessionary conditions in worse shape, relative to their competitors? This implies a loss of differentiation or competitive advantage and the loss of an ability to sustainably “over-earn”. This “loss” often corresponds with a long-term decline in market rating and market capitalisation. And its these companies we need to avoid.