Investor Insights

SHARE

Don’t sell! House prices must go up (unless you’re in Victoria)

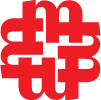

Recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has highlighted a significant concern echoed by analysts like Leith Van Onselen of Macro Business. According to the latest ABS data, Queensland’s population has grown by 124,200 residents in just the past year, culminating in March. This dramatic increase can be attributed to a combination of substantial overseas arrivals and a notable interstate migration trend.

Figure 1. The chart that matters. Net overseas migration

At the same time the population is surging (thanks to government policy), a downturn in housing construction has gripped the country.

Australia is witnessing a steep decline in new home sales, and industry experts foresee further challenges ahead. Tom Devitt, a senior economist at the Housing Industry Association, was recently reported to be predicting a slump in construction activity by 2024, intensifying existing housing shortages and making homeownership unattainable for many Australians. That forecast slump is clear from the approvals revealed by Figure 2., below. He pinpoints the downturn’s catalyst as the significant interest rate hikes initiated by the reserve bank of Australia (RBA) in May last year.

Most states have reported considerable decreases in new home sales over the three months to August. Specifically:

- Queensland recorded a 52.3 per cent drop compared to 2022,

- New South Wales experienced a 48.4 per cent reduction.

- Victoria and South Australia saw their sales decrease by 37.2 per cent and 26 per cent, respectively, however,

- South Australia noted a significant 35 per cent surge in sales in July, and finally

- Western Australia registered a 17.3 per cent increase in sales.

Helping to explain the South Australian experience is that government’s initiatives, such as the recent land release for housing and abolishing stamp duty for first-time homeowners purchasing new builds.

The Australian housing crisis will arguably be most keenly felt in the sunshine state as it grapples with its own, particularly intense, booming population and simultaneously and equally dramatic stagnating housing development.

A half-yearly 2023 report published by the Charter Keck Cramer consultancy (CKC), and reported by Macro Business, adds to the unease, forecasting a potential annual surge of up to 20 per cent in Brisbane’s weekly rents and new apartment prices over the next couple of years. For what it’s worth, I think it may be much more than that!

Such a surge threatens to further strain an already tight rental and housing market.

Brisbane, in particular, finds itself under the microscope in the CKC report. The city’s housing situation is described as potentially the most severe among Australian cities.

An underlying cause might be the Queensland government’s underestimation of true population growth. Net overseas migration figures (see Figure 1.) have clearly surpassed prior government predictions, suggesting more substantial housing demand than what is currently planned for.

CKC’s national executive director of research, Richard Temlett, is reported to have candidly remarked, “It may take us a decade or more to truly find a solution to this burgeoning housing challenge.”

Other major cities aren’t immune either. Sydney and Melbourne have reported unprecedented spikes in overseas migration, emphasising a national trend. The overarching narrative suggests that unless Australia revises its immigration policies to align with its infrastructural and housing capacities, the country might find itself in a perpetual rental and housing crisis.

Unlike so many other crises, this one will work to keep prices elevated rather than depressed. If you own an apartment or a house, modest returns can be reasonably expected, with some areas generating significant returns. Of course, how those returns are distributed will very much be determined by the relative attractiveness of the tax rules imposed by each state. Victoria, for example, can be expected to fair worse as investors turn their back on that market after Dan Andrews, (whom I am told relishes the moniker, Chairman of the Great Southern Province), imposed a 7.5 per cent tax on short-stay accommodation rentals in a classically socialist attempt at a solution to the housing crisis there.

Figure 2. Private residential building approvals

Houses and apartments can’t be built unless development proposals are approved by either local councils or state authorities, depending on the size of the project. As Figure 2., reveals approvals are depressed, meaning future building activity will be too. Indeed, total Australian building approvals are levels last seen in 2005 and 2011, when Australia’s total annual immigration was 143,000 and 169,000 people respectively.

Today, immigration is reaching record levels. According to the ABS, in 2022, there were 619,600 overseas migration arrivals and 232,600 departures, resulting in Australia’s population growing by 387,000 people from overseas migration. That number will be higher in 2023.

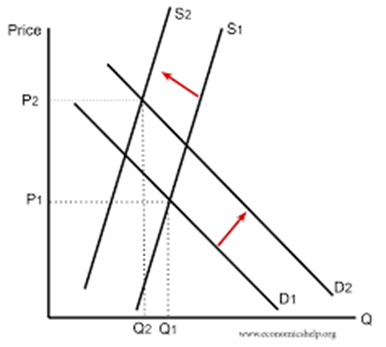

Figure 3. Economics 101. Rising demand and falling supply

A quick economics lesson: Figure 3., reveals what happens when demand rises (D to D2) and supply falls (S to S2). The equilibrium point, which is the intersection of supply and demand, rises and prices go up from P1 to P2. P is price. According to Economics 101, the item that balances rising demand and falling supply is prices. Prices therefore must go up.

You can put away all your real estate agent forecasts and commentary from various experts. A year 11 business studies student can tell you property prices have to rise, or at least remain elevated if they have already risen.